Leaving Cert Economics: Ireland’s Economy

Click here to download a workbook on Ireland’s Economy so that you can add your own notes.

Connecting Brilliant Minds in Economics and Finance

by Frank

by Frank

Jennifer Murtazashvili is professor and director of the International Development Program at the Graduate School of Public and International Affairs at the University of Pittsburgh.

Her research explores questions of governance, public administration, and local institutions with a geographical focus on Central and South Asia and the former Soviet Union.

Jennifer’s first book, Informal Order and the State in Afghanistan, was published by Cambridge University Press in 2016.

A second book, Land, the State, and War: Property Rights and Political Order in Afghanistan (with husband Ilia Murtazashvili) is under revision.

Professor Murtazashvili’s current projects include research related to the (unexpected) role of bureaucracy in conflict-affected states, local governance and social institutions in Central Asia, and the geopolitics of Central Eurasia.

Jennifer also serves as an elected member of the Central Eurasian Studies Society executive board.

Her research reflects extensive field experience where she has lived on the ground for five years in former Soviet Central Asia and about three years in Afghanistan.

She has collected diverse types of original data employing a wide range of tools to answer important policy questions ranging from ethnographic fieldwork, interviews, focus group discussions, public opinion surveys, as well as field experiments.

In addition to academic endeavors, Professor Murtazashvili remains deeply engaged in public policy.

For three years, she served as a democracy and governance officer for the U.S. Agency for International Development in Tashkent, Uzbekistan, a Peace Corps Volunteer for two years in Samarkand, Uzbekistan, and for more than a year as a Senior Research Officer at the Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit.

Jennifer has also served as an advisor for a number of organizations including the World Bank, U.S. Agency for International Development, U.S. Department of Defense, the United Nations Development Program, and UNICEF.

She has a Ph.D. in Political Science and a M.A. in Agricultural and Applied Economics from the University of Wisconsin-Madison

Informal Order and the State in Afghanistan by Jennifer Murtazashvili

The Underground Girls of Kabul: In Search of a Hidden Resistance in Afghanistan by Jenny Norberg

Private Truths, Public Lies: The Social Consequences of Preference Falsification by Timur Kuran

Charlie Wilson’s War : The Extraordinary Story of How the Wildest Man in Congress and a Rogue CIA Agent Changed the History by George Crile

Paradigms and Sand Castles: Theory Building and Research Design in Comparative Politics (Analytical Perspectives On Politics) by Barbara Geddes

If you’re a fan of the podcast and would like to show your support in anyway, please check out my Patreon page at www.patreon.com/economicrockstar where you can sign up for any of the awards for as little as $1 a month or you can simply follow me on Instagram, the Economic Rockstar Facebook page or on Twitter or simply recommend the show to a friend, especially if they have never had the opportunity to study economics.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

by Frank

by Frank

Edward Castronova is professor of Telecommunication and Cognitive Science at Indiana University Bloomington. He pioneered the study of how money,value, and property flow inside online games like Everquest

Castronova’s paper Virtual Worlds: A First-Hand Account of Market and Society on the Cyberian Frontier became the most downloaded paper in the entire database — beating out works by dozens of Nobel laureates.

If you’re a fan of the podcast and would like to show your support in anyway, please check out my Patreon page at www.patreon.com/economicrockstar where you can sign up for any of the awards for as little as $1 a month or you can simply follow me on the Economic Rockstar Facebook page or on Twitter or simply recommend the show to a friend, especially if they have never had the opportunity to study economics.

http://www.patreon.com/economicrockstar

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

by Frank

Professor, George L. Argyros Endowed Chair in Finance and Economics, Professor of Economics and Law

Dr. Vernon L. Smith was awarded the Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences in 2002 for his groundbreaking work in experimental economics.

He has joint appointments with the Argyros School of Business & Economics and the Fowler School of Law, and is part of a team that will create and run the new Economic Science Institute at Chapman.

Dr. Smith has authored or co-authored more than 300 articles and books on capital theory, finance, natural resource economics and experimental economics.

He serves or has served on numerous board of editors including the American Economic Review, The Cato Journal, Journal of Economic

Behavior and Organization and the Journal of Economic Methodology.

Dr. Smith is a distinguished fellow of the American Economic Association, an Andersen Consulting Professor of the Year, and the 1995 Adam Smith Award recipient conferred by the Association for Private Enterprise Education.

Dr. Smith completed his undergraduate degree in electrical engineering at the California Institute of Technology, his master’s degree in economics at the University of Kansas, and his Ph.D. in economics at Harvard University.

If you’re a fan of the podcast and would like to show your support in anyway, please check out my Patreon page at patreon.com/economicrockstar where you can sign up for any of the awards for as little as $1 a month or you can simply follow me on the Economic Rockstar Facebook page or on Twitter or simply recommend the show to a friend, especially if they have never had the opportunity to study economics.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

by Frank

Dr. Jaclyn Lindo is an economics instructor at the University of Hawaii’s Kapiolani Community College where she teaches principles-level courses and advise the Economics and Business Club.

teaches principles-level courses and advise the Economics and Business Club.

Dr. Lindo flipped all of her courses using a combination of publisher-produced videos and her own problem-based, collaborative in-class assignments. She strives to make her course material as relevant to students’ experiences and interests by using pop culture as well as integrating local issues.

Jaclyn will be part of the first cohort of faculty to integrate land-based learning into their pedagogy with the aim of promoting learning that is rooted in Native Hawaiin values, place-based research, and community engagement to understand community needs.

Jaclyn previously lectured on health economics at the University of Hawaii at Manoa, continuing with her expertise as the senior health economist at Hawaii Health Information Corporation. While there, Jaclyn researched healthcare policy and outcomes at the national and local levels.

Jaclyn completed her PhD at the University of Hawaii at Manoa in 2011.

Show Notes Coming Soon!

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

by Frank

Asgeir B. Torfason is Assistant Professor in the School of Business at the University of Iceland where he teaches  Finance, Accounting and Financial Statement Analysis. Asgeir is also Postdoc Research Fellow, as well as an Assistant Professor at Gothenburg Research Institute.

Finance, Accounting and Financial Statement Analysis. Asgeir is also Postdoc Research Fellow, as well as an Assistant Professor at Gothenburg Research Institute.

Asgeir defended his PhD at Gothenburg University in May 2014 with dissertation: Cash Flow Accounting in Banks – A study of practice.

His research combines bank management, finance theory, monetary economics and accounting studies.

Previous research has focused on asset values and long-term investment in real estate, a field where Asgeir has extensive practical experience, covering the Nordics as VP for a REIT listed on NYSE.

Prior to that he worked in university management after getting an MBA from Norwegian Business School in Oslo, and studied earlier Philosophy and Economics in Iceland.

In this episode, Asgeir mentions: Iceland’s economy, IT bubble, Tulip Mania, banks, capital controls, devaluation, tourism, resources, trade, cashflows, assets, liabilities, revenue, equity, income statements, bankruptcy, lending, negative cashflows, money multiplier, reserve requirement, central banks, quantitative easing, swap lines and housing bubbles.

In this episode, Asgeir mentions: Joseph Schumpeter, John Maynard Keynes, Hyman Minsky, Perry G Mehrling,

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

by Frank

Stephen Kinsella is a Senior Lecturer in Economics at the Kemmy Business School, the University of  Limerick in Ireland and a Research Fellow at the Geary Institute at University College Dublin. He is currently visiting Professor of Economics at Université Paris.

Limerick in Ireland and a Research Fellow at the Geary Institute at University College Dublin. He is currently visiting Professor of Economics at Université Paris.

Stephen has two PhD’s, is well published in many Economics Journals and has won several grants worth around 1.5 million Euro.

Stephen’s area of expertise is in the study of the Irish and European economies.

He has written 4 books:

Stephen is a weekly columnist for the Sunday Business Post newspaper and he also has his own website stephenkinsella.net which is amazingly rich in content, covering issues on the Irish and European economy as well as material he covers in his lectures.

In this episode, Stephen mentions: stock flow consistent models, rent controls, GDP, wealth, consumption, government expenditure, investment, net exports, debt-to-GDP, stock of unemployed-to-flow of the labor force, taxes, austerity, QE, pro-cyclical policy, unemployment, automatic stabilizers, Brexit, foreign direct investment, hyperinflation, purchasing power of money, housing, pricing mechanism and money supply.

In this episode, Stephen mentions: Wynne Godley, Lance Taylor, Marc Lavoie, Kevin O’Rourke, Philip Lane, Dermot McAleese, Edward Nell, Carmen M. Reinhart, Kenneth S. Rogoff and Joseph Stiglitz.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

by Frank

This weeks episode of the Economic Rockstar podcast features the Australian economy. There is talk amongst economists, analysts and commentators, be it speculative or not, that the Australian economy or it’s housing market will implode within the next 12 to 18 months. I am joined with Professor Steve Keen who explains why the property market in Australia will crash, taking its economy down with it.

Given the nature of this podcast, I cannot ignore the discussion that is taking place on what’s going on with the Australian economy. To be honest, a listener to this podcast who is living in Australia contacted me on what’s going on there, and he and his friends are taking precautions in the event of a collapse in house prices. I also have Irish friends who emigrated to Australia once the financial crisis hit. These young men travelled from Ireland to Australia and know, with first-hand experience, how an economy and housing market performs prior to a crash. They, like others, are tuned into events that lead to a bursting of a bubble. Doubters and cynics may claim that this is an unscientific approach to analysing the market, but shouldn’t we also consider non-numeric data in the form of intuition and gut-instinct?

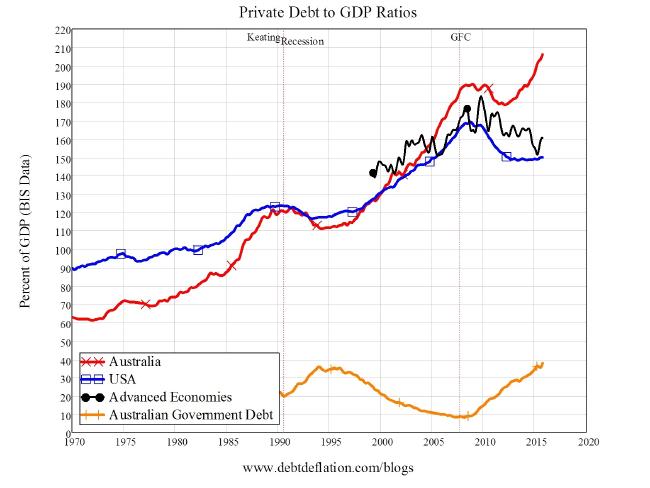

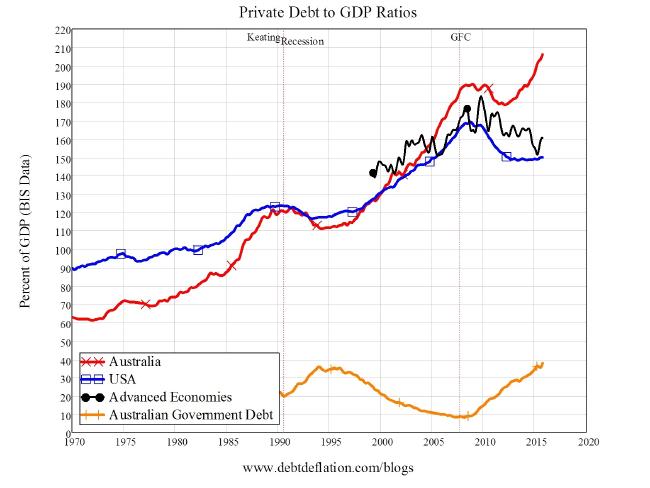

Economic data is also available today that supports the claim that the Australian housing market is on the brink of collapse. Australia’s private debt to GDP is currently at 210%, the highest in its history. Such high ratios were experienced by other developed economies prior to the Great Financial Crisis which pushed them into recession following a property market crash. Is Australia different? Australia is most definitely not immune to such crashes.

Did you know that house prices plunged 30 percent or more in NSW and Victoria in the 1890s and 1930s — the biggest such reversals in Australia’s history — the result was bank collapses and mass unemployment. Could this be repeated?

So a question I’d like to pose would be ‘What’s worse? Carrying out a pre-mortem or a post-mortem. Both can have very damaging repercussions for an individual if decision-making was wrong. A pre-mortem forces someone to take a contrarian view of the economy. They can then write up a checklist of possible events that could materialize and the actions that need to be taken today to assure a minimum negative impact.

Can a person’s pre-mortem be evidence of over-confidence or can it be a deep-rooted intuitive reading of all the vital signs that are indicating something sinister that had once played out before? After-all, many economies have experienced busts and housing market crashes. No country is immune to these events. What precipitates a housing crisis has been explained on numerous occasions in the economic literature, albeit for different time periods, economic cycles and, dare I say, personal viewpoints and data collection methods.

So, should we ignore the intuition and gut instinct of those in tune with the development of an economy and its actors? Is Australia different to other economies? After all, Australia hasn’t experienced a recession since 1991 – 25 years ago!

Should we ignore or heed the warnings of the naysayers? Can intuition be considered a valid barometer to understanding how events are likely to unfold in an economy?

Nobel laureate Danial Kahneman who, in an interview with McKinsey and Company, considered the intuition of professionals in the decision-making process. Kahneman stated that:

There are some conditions where you have to trust your intuition. When you are under time pressure for a decision, you need to follow intuition. My general view, though, would be that you should not take your intuitions at face value. Overconfidence is a powerful source of illusions, primarily determined by the quality and coherence of the story that you can construct, not by its validity. If people can construct a simple and coherent story, they will feel confident regardless of how well grounded it is in reality.

Despite this statement being considered under a different context, it could easily be applied to the economy since professionals are a subset of the population and their decisions can impact the local and wider economy.

Let’s break this statement down.

Kahneman states that “When you are under time pressure for a decision, you need to follow intuition.” In an economy or a housing market that is performing so well like Australia today, time doesn’t play a central role for the majority of those involved in the decision-making process. Of course, well-timed investments can be the difference between a gain and a loss.

Typically, in good times, people can become blind-sided and focus on the positive news. The economy will continue on as it has always done. The housing market will continue performing strongly and it will always be a good time to buy property. When you’re in the thick of it, the good times keep rolling. You want to participate in any market whose assets are experiencing capital appreciation. The majority of people make decisions based on past performance. The housing market in Australia has grown to unprecedented yet worrying levels.

Any negative news or commentary is largely dismissed and the bearers of the bad news are typically criticised and vilified. Humans have the ability to forget their past failings and fallibilities and repeatedly make the same mistakes over and over again. Economic history shows us the misconceptions and judgemental errors made by humans from Tulip Mania to the South Sea Bubble and the dot-com crash. If the housing market was to implode in Australia, time would become the main focus as people will rush to the exits. Housing is not as liquid as stocks or cash and a housing crash will be the result.

Participants in the Australian housing market are accumulating dangerous levels of private debt, never seen before in its history. Private household debt now stands at 210% of GDP. This is an unhealthy level for any economy to be in and one that was highlighted by Professor Steve Keen in his blog debtdeflation.com and his book Debunking Economics. Professor Keen warned of the risks to many economies and their housing market prior to the Great Financial Crisis.

Australia’s Private Debt to GDP Ratio as Calculated by Professor Steve Keen

He also warned about Australia’s economy at the time but Australia avoided a recession. Policy initiatives at the time, as well as the availability of credit, rising commodity prices (of which Australia benefits from), a demand for housing stock from mainland China and an appetite for risk to avail of the speculative gains being made in an accelerating property market has resulted in Australia being different to other economies.

Australia is the darling economy and a perceived role model on how to maintain economic growth. These positives led to immigration rising as a demand for employment increased. And as we know, when jobs are created, income levels rise feeding the demand for goods and services. Eventually, confidence rises and speculative purchases are made. When the desired expectations to these speculative purchases come to fruition, then people become overconfident.

As Kahneman stated earlier, “Overconfidence is a powerful source of illusions, primarily determined by the quality and coherence of the story that you can construct, not by its validity. If people can construct a simple and coherent story, they will feel confident regardless of how well grounded it is in reality.”

RBA economist Peter Tulip last year suggested Australian housing could be as much as 30 percent undervalued. This type of commentary is not helpful in a market that is overheating and when participants or would-be buyers are excited about capital appreciation despite being negatively geared. This is definitely a new take on Tulip Mania!

The same economist, Peter Tulip, in a 2007 working paper for the OECD, wrote about how safe Iceland’s economy was and that it’s banking system was secure and stable, and that it’s housing market should be liberalised and opened up to competition.

Today, there are reports of being able to borrow 10 times your pre-tax income to purchase a property. This is not a healthy situation for anyone to be in, including banks.

Australia has an active sub-prime mortgage market. Interest rates are low at 2% (yet they could go lower as we have seen elsewhere). Perhaps the Royal Bank of Australia isa keeping a 2% cushion in the event of implementing a loose monetary policy in the event of a crash. Unfortunately, this type of stimulus will not work as households will be required to pay down its debt and the economy could enter into a Japanese-style era of stagflation.

Australia is dependent heavily on its commodities, hence the dollar being know as a commodity currency. There is a continuing drop in resource prices and commodity-dependent companies such as Rio and BHP are in trouble.

Banking shares have dropped and could be seen as ominous of what’s to come. Are there people in the know? Are they liquidating their holdings? Check out what happened to many of the leading US and European banking shares prior to October 2008 – the official start of the Great Financial Crisis. They were already on a downward trajectory.

Is China slowing down? The Chinese have also accumulated high levels of private debt and their private debt to GDP ratio is similarly high to Australia’s. If Chinese investment in the Australian property market stops, then the market could implode.

There is an overwhelming supply of apartments in Brisbane, Melbourne and Sydney. Many of these apartments lie vacant and buyers are expecting their negatively geared position to be offset by further capital appreciation. Also, immigrants have proven to be very mobile. When signs of a weakening economy materialise, they will emigrate leaving a slump in housing or rental demand. Owners will fail to meet repayments as the main source of their rental income will disappear.

Put simply, in the words of Professor Steve Keen, Australia’s housing market is a Ponzi scheme and those that got in first will be the winners while all of those who got in over the last few years will suffer.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

by Frank

This is a commemorative episode celebrating the 100 year anniversary of Ireland’s 1916 Easter Rising in which the Proclamation of the Republic was read by Padraig Pearse at four minutes past noon on Easter Monday, April 24th, from the steps of the General Post Office on Sackville Street (now known as O’Connell Street). The document proclaimed Ireland’s independence from Great Britain.

How was Ireland’s economy performing in 1916 and how far have we come 100 years on?

Ireland in 1916, consisting of 32 counties, was ruled by Great Britain. The 32 county economy experienced a period of unprecedented prosperity mainly due to the positive economic effects of the First World War.

However, since the Great Irish Famine of 1846, Ireland experienced mass emigration and large numbers of deaths. The laissez-faire economic ideology was a failure. From the period 1851 to 1916, over 5 million Irish citizens emigrated reducing the population from a peak of approximately 8 million to 3 million.

The Irish economy was ruled by Great Britain and its economy became increasingly tied to trends in global markets. The cost of living increased and there were some rises in living standards. These were subject to sharp declines due to the recessions of 1859 to 1863 and 1877 to 1880. Poverty was widespread and tensions between landlords and tenant farmers escalated. Despite this poverty, Irish living standards were above most of Eastern and Central Europe but income levels remained below the UK and the US.

Ireland’s economy became increasingly reliant on four main industries: Agriculture, Linen production, Shipbuilding (where the Titanic was built) and Brewing and Distilling. However, agricultural exports were heavily dependent on Great Britain and Shipbuilding was dependent on an outdated industry. For example, it wasn’t long after the First World War that the Irish Shipbuilding industry collapsed.

The First World War of 1914 brought about a period of prosperity for Ireland, due to the increased demand for food, linen and ships that were directly linked to the war effort. However, this prosperity was not shared by all.

So what did the Irish economy of 1916 look like compared to its economy today 100 years on?

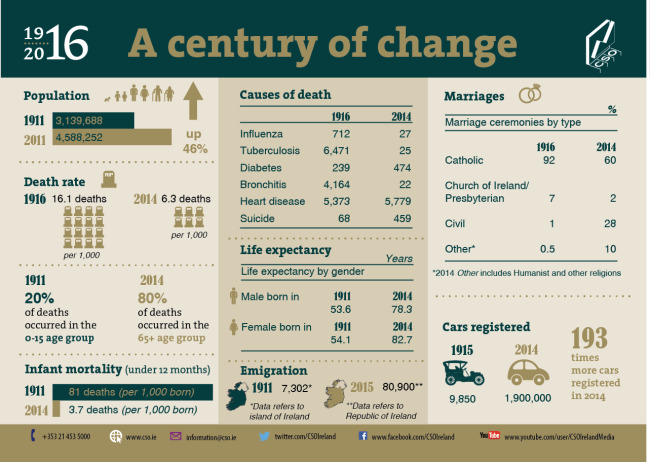

The population of Ireland in 1916 was one of the lowest recorded in its history. According to the population census of 1911, the population stood at just 3.14 million. It represented a country devastated by death caused by the famine over a half century previous and the subsequent mass emigration that ensued.

A 9-year-old Irish immigrant laborer shucks oysters in front of his foreman in the U.S. in 1911. pic.twitter.com/cOKICWk8Ta

— HISTORY (@HISTORY) April 12, 2016

Today, Ireland’s population has recovered to 4.59 million, an increase of 46%. However, many have emigrated due to the financial crisis of 2007, most notably Ireland’s youth. We have reverted to being a net emigration population after a period of becoming a net immigration population, attracting workers from overseas as well as bringing Irish people home.

Emigration for the whole island of Ireland in 1916 was 7,366 or 17 per 10,000 of the population. This had fallen from a substantial level before the outbreak of the Great War. The latest data for 2015 shows emigration for the Republic of Ireland at 80,900 representing 175 per 10,000 of the population.

Emigration in 1916 consisted of 5,580 females and only 1,786 males. This I found surprising.

The four main destinations for Irish emigrants in 1916 were the US, the UK, Canada and then Australia.

In 2015, the UK was the main destination for Irish emigrants. Only 7% of emigrants went to the US in 2015 compared to 58% emigrating in 1916.

The Irish diaspora abroad is quite large. Despite being a small island off Western Europe, Irish smiles have been welcomed all over the world. Ancestry can be traced back to Ireland particularly for those living in the United States, the UK, Argentina, Australia and Canada.

Today, it is estimated that there are 80 million people of Irish descent living around the world today. Other that the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland, Montserrat in the Caribbean is the only other country where St. Patrick’s Day is a public holiday.

Montserrat is known as the Emerald Isle of the Caribbean and it’s Irish heritage dates back to the 17th century when the island became a safe haven for the Irish who were originally sent to the Caribbean as slaves by Great Britain’s leader Oliver Cromwell. A census in 1678 showed that more than half of the population on the island were Irish.

According to records for 1911, the life expectancy for a male born in Ireland was 53.6 years and for a female 54.1 years. Today, a male born in Ireland has a life expectancy of 78.3 years and a female 82.7 years.

Despite the period of prosperity, Ireland remained divided in terms of the gap between wealth and poor. Much of rural Ireland in the west of the country lived as an agrarian society, dependent on agriculture for a living. Living standards were much lower relative to other parts of the country.

Urban areas did not escape the ravishes of poverty. Inequality was more prevalent in urban towns, particularly in Dublin city. Despite a boom in food and linen exports in 1916, the Irish poor remained hungry.

Henrietta Place, Dublin 1913. The flight of wealth to the suburbs often meant an escape from inner city squalor.

Poverty levels in Ireland today are at 8% with households consisting of one adult and one or more dependent children considered most at risk. Rural Ireland, including the West of Ireland, has a higher incidence of poverty than the rest of the country. As the saying goes, things change but always stay the same!

Many adults and children perished due to influenza, bronchitis and tuberculosis. These were the leading causes of death in Ireland along with heart disease. Today, heart disease is the leading cause of death in Ireland with few incidences of death from the other forms. The number of deaths by suicide that was officially recorded in 1916 were 68 compared to 459 for 2014, This represented 10 per 100,000 of the population compared to approximately 2 per 100,000 of the population.

Ireland’s macro economy of 2016 is showing remarkable progress since it’s recession, bailout and financial crisis. The Irish have a love affair with housing. Perhaps it has its roots in history where many people were evicted from their homes during the Great Irish Famine.

During the boom from 1998 to 2007, Irish house prices soared only to come crashing down once the crisis hit. At its peak, over 90,000 houses were built but today only 11,000 houses were completed. The Irish housing market is under immense stress with demand outstripping supply. This shortage is resulting in much higher rents than what was recorded during the boom period. House prices are recovering but recent government legislation is making it difficult for landlords who are selling their property or evicting their tenants in order to capture the higher rental yields. Ireland is undergoing a housing crisis in today.

In 1916, Ireland experienced a severe housing crisis. Dublin and other cities became infamous for the living conditions of its citizens. The tenements, where many impoverished families lived, marked a bleak period in recent Irish history.

Multiple families shared large terraced houses with extremely poor sanitary and hygiene conditions. It was estimated at the time that 20,000 families in Dublin occupied single rooms and in some cases with other families. Family sizes of 8 or 10 children were not unusual. There were cases of 104 people occupying a single house built to accommodate one family.

A Tenement Room on Francis Street, Dublin in 1913

Many evictions took place as families fell behind in rent. Facing starvation, children queued for bread which was handed out by religious orders. Many people in the West of Ireland emigrated due to food shortages and abandoned their homes. Despite many empty homes in the rural parts of Ireland, many families suffered homelessness, extremely poor living conditions and starvation.

Due to the housing crisis that Ireland is experiencing today in 2016, there are some echoes of the past. Homelessness has jumped 100% since January 2015. Over 700 families are living in emergency accommodation in hotels and guest houses. Evictions are up significantly and there are currently 17,000 people in the courts who are at risk of losing their homes. Food parcels are being handed out each week and the number queuing is rising.

The Irish economy in 1916 was transitioning toward becoming an industrial nation. It was by no means considered backward and was in fact placed in the group of middle-ranking industrialised countries along with the Netherlands, the Scandinavian countries, Italy and Portugal. 26.8% of workers in 1911 worked in manufacturing jobs compared to 8.6% in 2011.

An estimated 150,000 men had joined the British army and many men and women went to the UK to find employment in munition factories and hospitals. Wages had increased during this time.

Almost 50% of the working population were employed in the Agriculture sector in 1911. This compares to just 4.9% in 2011.

In 1911, 8.8% of the labour force in Ireland worked in the professional group of occupations. By 2011, these workers now account for over 40% of the Irish workforce.

Ireland’s unemployment rate today is 8.8% coming from a recent high of 14.4%. It is unsure what the level was in 1916.

Ireland in 1916 mostly consisted of indigenous industries. 85,000 workers were employed in linen production with over 18 million pounds (weight) of linen yarn and 112 million pounds (weight) of finished linen goods exported. Prior to the outbreak of World War I in 1914, about 70% of these exports were to the United States of America. However between 1914 and 1918, linen was in great demand for military purposes by the British Army for items such as tents, haversacks, hospital equipment and aeroplane fabric.

Today much of its traditional industry gone today. Very few linen manufacturers and weavers exist today. To bring my own personal family history into this story, my family remains one of a few linen weavers in Ireland today, producing the best Irish linen in the market with exports to countries that include Japan, the US and Italy. I’m personally proud of my father for what he has achieved and for extending the Irish tradition of producing the finest linen in the world.

Ireland is considered a small open economy and the UK still remains one of our largest trading partners. The Irish economy attracts many multinationals companies to locate here. In 2016, Ireland ranks among the top countries regarding industrial competitiveness and ease of doing business.

The Guinness brewery was the main brewery in Ireland and in 1916 it had the largest output of any brewery in the world, brewing more than two-thirds of all beer brewed in Ireland.

Cask Yard St. James’ Gate Brewery 1906 – 1913

The largest exporting sectors in Ireland during 1916 were woollens, brewing, butter, bacon, poultry, cattle, cotton goods and linen. The sectors that were in decline included horses, whiskey, pigs and sheep.

Ireland had a trade surplus of 1.5 million pounds (and a balance surplus of 11.1 million pounds) in 1916. For the latest data today, which is January 2016, Ireland is operating a trade surplus of 4.99 billion euro. Ireland’s largest exporting sectors are Medical and pharmaceutical products (representing 27% of total exports), Office machines and automatic data processing machines, and Food and live animals (representing 7.8% of our total exports).

The EU accounts for 56% of the total value of Irish goods exported. Belgium is Irelands largest export trading partner accounting for 15% of the total value of goods exported.

Great Britain remains Ireland’s single largest source of imports with 25% of the total value of goods imported to Ireland.

The USA remains Irelands largest non-EU destination for exports and imports.

According to research by Kevin O’Rourke of the Department of Economics at University College Dublin a proxy measure for GDP per capita in Ireland was estimated to be 32.50 in 1913. This was based on a GDP estimate of 150 million. To put this into some context, the estimated GDP per capita in 1864 was 12.50 with GDP estimated at 60 million – over a 160% increase in nominal terms between the Famine and the Great War. Irish GDP per capita converged on the UK average during this time.

According to the International Geary-Khamis dollars, Ireland’s GDP per capita in 1913 was $2,736 whereas the US GDP per capita was $5,301 and the UK’s at $4,921, almost twice that of Ireland’s. This seems to suggest that incomes had yet to converge with those in Great Britain.

Eden Quay displays the bustle of turn of the century Dublin city life

Ireland would have been considered one of the poorest Western European countries along with Greece, Italy, Portugal and Spain – yes there’s that familiar acronym of the financial crisis.

Today, Ireland is considered one of the richest countries in the world with GDP per capita of just under $49,000, placing the country in 10th position, with the US in 9th and the UK in 19th according to the World Bank.

GDP for Ireland was $11.9 million but this collapsed to $7.8 million by 1921 perhaps due to the Irish civil war. It was only in 1960 that Ireland recovered to pre-1916 levels.

There were 9,850 cars registered in Ireland in 1915 with now over 2 million registered today.

Due to the outbreak of the First World War in 1914 and the resulting scarcity of goods, inflation in Ireland increased considerably by 200% over the wartime period as measured by the wholesale price index.

Unless wage inflation was outpacing price inflation in 1916, which is very unlikely, families must have experienced a real reduction in the purchasing power of their £.

These increases in prices were also due to Government policy which increased taxes and duties on various products.

The retail price of butter, tea and eggs were expensive in 1916. For example, the price of a pound of butter then would have cost 7 euro 35 cent updated to today’s consumer price index compared to today’s price of 2 euro 79 cent.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Only Available to Economic Rockstar Subscribers

Powered by OptinMonster